A tight row of cedars shelters the path leading from the house to the barn where Henry Stanford Strader took his life on a Wednesday morning in December 1926. After speaking with his brother-in-law, he lit a cigarette, walked up the trail behind the cedars, and shot himself with a rifle in a rented barn. While the town doctor and the coroner rushed to the site, news traveled in the other direction, reaching villages along the St. Lawrence River. The local papers provided the insensitively gory details next to advertisements for Christmas sales at the local department stores and jewelers.

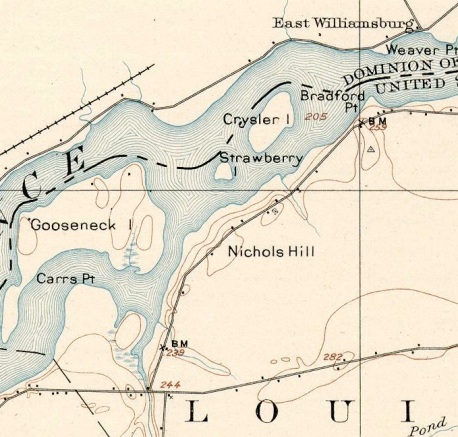

Stanford died at the top of a low sandy mound in the town of Louisville (pronounced Lewisville) called Nichols Hill, named for a more successful farmer from the previous century. Today, the hill is Nichols Hill Island, created by a trick of gravity, geology, and engineering when the Moses-Saunders Power Dam began operation in 1958, creating the St. Lawrence Seaway. The island stands in the middle of an archipelago created from similar hills, a series of sand dunes formed after the last glaciers left the St. Lawrence Valley millennia ago.

Today, stone and concrete foundations buried in honeysuckle mark the former location of what was, for a very short time, the Strader family home. Before the dam began operation, laborers dismantled hundreds of houses and barns along the river. They moved cemeteries and cut down large trees, but left behind the stumps and sawed-off utility poles, the pavement and the foundations. The arrow-straight road that once connected these islands ducks into the water and emerges again on the next island, but its ghost is visible beneath the surface on satellite images of the Seaway. Now, scattered daffodils and day lilies, a rogue patch of rhubarb, two parallel mature rows of maples, and the cedar hedgerow mark the site, a jarring reminder of home in what became a remote, isolated forest since the dam flooded the valley. In other places on the island, scraggly orchards and knotted Concord grapevines still bear delicious fruit.

The New York Power Authority recently concluded a multi-year project to reconnect these islands with new causeways, largely following the route of what locals called “the river road.” They also installed water control structures to maintain water levels between the islands and the mainland, part of a habitat improvement and wildlife management project. The recent work on the island involved a detailed archaeological survey to ensure no historic resources would be impacted by the project. The project included a new road through what was once the Straders’ front yard. The most direct access to the island was by boat from the nearby marina. Otherwise, it was a long ride in a four-wheel drive vehicle to the end of a causeway, followed by a two-mile hike. The Lawrence farm, where Stanford shot himself, sat at the top of a hill at the end of the line, as far as you could get from where you first started.

Before the hill became an island, historical documents suggest Stanford Strader’s experience of loss and economical struggle led to a personal isolation. Stanford grew up in Matilda in Ontario’s Dundas County, a small farming town on the north bank of the river, where the extended Strader family owned a cluster of adjoining farms. In 1909, at the age of 20, eager to start his own family and farm, Stanford married 18-year old Bessie Kirkwood from the neighboring town of Williamsburgh. But ten years later, Bessie died, leaving Stanford with two young sons. He quickly married Beatrice Courtney, also from Williamsburgh and very young, and moved across the river in December 1922 to the town of Waddington. He left one son behind at the new hospital for crippled children in Montreal, where the Shriners had built a new school on the slopes of Mont Royal.

Newspaper accounts from New York’s North Country follow Stanford’s frequent moves between rented farms in the years leading up to his suicide. By the winter of 1924, Stanford and his family moved onto the Whalen farm, sharing a house for three months with the previous tenant until the new lease began. The Straders did what they could to supplement their farming income and continue to pay the rent. In October 1924, the family sold Scotch collie puppies through an advertisement in the local paper, a breed popularized in the United States through the stories of Lad by Albert Payson Terhune at the beginning of the century.

The Straders moved in July 1926 to the Samuel Lawrence farm on Nichols Hill. The Lawrence barn, a state-of-the-art facility, burned to the ground the previous year, destroying all of its largely uninsured contents and livestock and leaving just the cut hay drying in the field. Just a few weeks before their move to the rebuilt Lawrence farm, Beatrice’s sister, Marion, married Leo Hume, a local farmer. Later that year, Leo found Stanford dead in the barn on the hill, a gun lying on the floor by his side.

By the Friday after his death, Stanford’s family removed his body back to Canada and buried him in a Williamsburgh cemetery beside his first wife under a red granite headstone. Beatrice moved with the children to a neighboring town in New York and in April 1927 a social announcement quietly reported her return to the river road to visit Marion and Leo with Orlen Shoen, a man she would eventually marry the following January.

It is the privilege of the archaeologist to experience and overcome isolation in both time and space. Archaeologists often uncover signs of past human habitation in unlikely places. By understanding more about the past landscape, archaeologists reframe our assumptions of what place means in cultural and historic terms. This helps us close the gap between the past and the present and understand how a place becomes a site, an archaeological concept known as a formation process. In most cases, a site representing some vignette of the past can seem cut off or irretrievable from our present surroundings. At Nichols Hill Island, modern engineering isolated houses and foundations, orchards and cemeteries, roads and hedgerows, and nature isolated them further, sealing a landscape away in a time capsule. Today’s incredibly remote and difficult to reach location was once part of a community of farms and families, where social announcements in the newspapers reported on out-of-town visits, personal accomplishments, and residents improving or failing from various illnesses.

The accidental discovery of Stanford’s story and his tragic decision just over a week before Christmas in 1926 emerged from a chance search in an online newspaper archive for Samuel Lawrence, the owner of the farm whose name appeared in a deed. From there, searches for “Stanford Strader” in newspapers and other documentation began to piece together his story: his child at the hospital in Montreal, Bessie’s death, his remarriage and hopeful move to the American side of the river, and a short career of tenancy before his death.

It takes some imagination and critical thinking to envision a landscape as it once appeared, to use the archaeological evidence at hand to build a model of what life was like during a particular time period. Nichols Hill was particularly hard to recover from the past, since Nichols Hill Island was at once a burden and a refuge, changed so drastically by the Seaway. Despite the long hike, sometimes aided by knee-high waterproof boots and chainsaws, the island offered little pleasant surprises at times. Delicious forgotten fruit, abundant wildlife, a passing container ship on the lunch break all provided pleasant reminders of the present in a place that could seem stuck in the past. Eventually, excavation and research combined to (metaphorically) reconstruct the site, placing the house, yard, wells, and barn back on the landscape in order to see the busy farming household amidst the overgrown foundations.

The cedar hedgerow was initially considered a functional part of the Lawrence farm landscape, distinctive silhouettes behind thick brush, once providing shelter on the walk between the house and the barn. In the North Country, they say during the winter that the only thing between you and the Arctic Circle is barbed wire and cows. Today, with a couple of miles of open water between the Lawrence farm and prevailing winter winds, the island can be particularly uncomfortable during the winter months.

Archaeologists use historical data to repopulate a place, to identify figures from the past and construct a narrative around people, places, and things. The emotional gravity of Stanford’s story, otherwise a very brief interval in the century-plus historic occupation of the farm, threatened to reframe the landscape’s interpretation. The line of cedars took on new, heavy meaning; instead of a sheltering presence, they became obscuring sentinels. Stanford’s emotional and psychological isolation in the past combined with the physical remoteness of the island chased away all of the other potential narratives of that place, distilling its entire history down to the details of that initial newspaper article in the Massena Observer: “After talking with his family, he lighted a cigarette and walked to the barn. The shooting occurred soon after.” Now, instead of answering typical archaeological inquiries, other questions came into focus. Where was the rifle: in the barn or the house? Did he leave through the front door? What view did the family have from the house to the barn? Could they see his lit cigarette through the cedars? Could they have stopped him? Empathy could make it hard to comprehend that this was not always an island.

Archaeologists in the field of cultural resource management typically adhere to a strict directive: to determine whether or not a federal project will adversely impact historic properties eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places. If an archaeologist finds a site during the initial stage and it cannot be avoided by the project, she must then evaluate the site for its potential for National Register listing. In order to do this, the archaeologist measures the site against four criteria. The first three criteria attempt to identify famous people or events associated with the property, or determine if the property exemplifies a building tradition or “the work of a master.” The fourth criterion, Criterion D, is quietly referred to as the “Archaeology Criterion.” This subjective category applies to historic properties “[t]hat have yielded or may be likely to yield, information important in history or prehistory,” which can be broadly applied to just about anything depending on the deftness of the argument. While the site on Nichols Hill Island was thought to be eligible for listing on the National Register under Criterion D, the project eventually avoided the foundations and scatter of artifacts in the yard surrounding the house. Honeysuckle and Virginia creeper are gradually swallowing up the site again.

The story of Stanford Strader, who was “well known in that section,” according to the local reporter, made the hill an island decades before the dam began operation. Measured against the four criteria, Stanford’s tragic demise does not yield information important to history with a capital H, no matter how painful the story. There is no National Register of Public Sorrow and Private Suffering. Archaeologically, like so many of the poor and marginalized in human history, it is impossible to assign any of the hundreds of artifacts collected from the site to the family’s five-month tenancy from July to December 1926. Even the three Super X .22 caliber cartridge cases found around the house could have come from an earlier tenant on the hill, or even an intrepid hunter visiting the island.

If Stanford’s story has anything to offer archaeology or to yield important information about history, it is that formation processes are not always purely functional. People leave their places and those places become our sites, but the reasons for leaving are complicated. While Stanford’s case was an extreme example, broken artifacts and abandoned landscapes are sometimes attached to emotional incidents and experiences of loss, grief, or rage. These incidents and experiences are largely unknowable, until they aren’t. Then they become the burden of the archaeologist to bear, a nagging reminder that we might not really know anything meaningful after all, unless it is spoon fed to us with a front-page story. Suddenly, a past landscape thought mastered and reconstructed boils down to a few moments and images with little to no archaeological footprint, like cigarette smoke glimpsed through cedars and the cavernous blast of a shotgun in a dairy barn.

Thanks to Hartgen Archeological Associates, Inc. and the New York Power Authority.

I am Henry Stanford Strader’s great granddaughter and would like to contact you if possible.

LikeLike

Great! Email me at coreydmcquinn@gmail.com and I’ll give you my phone number. Looking forward to speaking with you!

LikeLike

Great article, I’ve shared it today with my cousins – Beatrice was our Grandmother – Stanford was their Grandfather.

LikeLike

Thanks for reading, Sandra! I am working on a follow-up after speaking with Stanford’s great-granddaughter and grandson. Stay tuned.

LikeLike

Is there a way I can get in touch with you?

LikeLike

feel free to email me at sandifarina@yahoo.com

LikeLike